KHUGA KHEYL, Afghanistan -- It was near sunset when the tire on one of the armored vehicles blew out on the way back through the village of Khuga Kheyl this month. The U.S. Army convoy stopped dead in a narrow, rocky cleft between two small mountains. A gang of Afghan boys ran down a nearby slope toward the convoy as it jerked to a halt near the border with Pakistan.

That morning, Capt. Jay Bessey had warned his platoon not to waste time and to stay tight. There was word that a suicide attacker might try to infiltrate his small base in a remote district in the eastern Afghan province of Nangahar. There was also a rumor that Taliban forces may have planted more than a dozen bombs along the convoy's route near another isolated district close by.

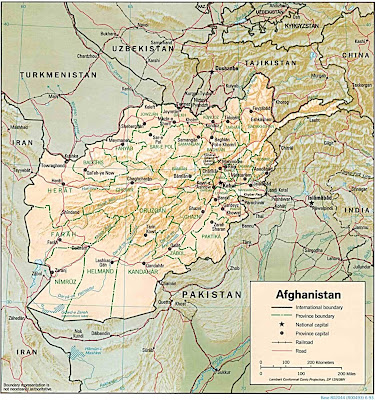

A flat tire an hour before sunset was the last thing Bessey needed. Yet there he sat, waiting for another unit to arrive with a spare. The incident underscored what all U.S. forces operating near the 1,500-mile-long border know: that the tyranny of the terrain is almost as formidable an obstacle to their goals here as the treachery of the Taliban.

The plan had been to meet with district tribal elders, deliver food aid and drop off a few benches and tables at a new school, creating a little local goodwill for U.S. efforts to stabilize the region, then get back to base before dark. Instead, Bessey sat listening to a village elder who had scrambled down the mountain from Khuga Kheyl with cups of tea and a laundry list of demands while the sun set on the convoy.

The mission in Khuga Kheyl was textbook counterinsurgency -- the kind of approach Gen. David H. Petraeus, the head of U.S. Central Command, has been trying to drive home to U.S. troops since he was a field commander in Iraq. There, under Petraeus, U.S. troops reached out to Sunni tribal leaders in the western province of Anbar to form community-based militias that helped reverse the tide of violence. The so-called Anbar Awakening, combined with an increase in U.S. troops, gradually created pockets of security in areas previously dominated by insurgents.

Petraeus, who is now in charge of the wars in both Iraq and Afghanistan, has said he plans to launch a similar approach this year in Afghanistan in a bid to retake the initiative from a resurgent Taliban. For that strategy to succeed, U.S. troops will have to broaden their presence in areas of Afghanistan where development has been slow, security precarious and confidence in the government of Afghan President Hamid Karzai limited.

Many of those areas lie in eastern Afghanistan along the border with Pakistan, which has become a gateway for the insurgency. With U.S. troop levels set to double to about 62,000 in Afghanistan in the coming year, American military officials here say the struggle to win tribal allegiances in remote, isolated places such as Khuga Kheyl will define the success or failure of Petraeus's plan. But in far eastern Afghanistan, where tribal loyalties often trump national interests, that is no easy task.

Rough, often impassable mountain terrain has made it tough to make inroads into border areas where thousands of Pashtun tribesmen teeter between support for Karzai and support for the Taliban. Last year, Afghanistan's eastern border provinces witnessed some of the bloodiest battles between coalition and insurgent forces. Insurgent incursions in the east increased by nearly 45 percent in 2008, according to the U.S. military. And many of the 151 U.S. troops killed last year died in combat in areas bordering Pakistan.

The conditions have made for a tense atmosphere for Bessey's men in the 6th Squadron, 4th Cavalry Regiment, based in Fort Hood, Tex., but he has pushed hard to counter their fears. "I try to tell our guys, 'You know, we're not going to win this thing by killing people,' " Bessey said. "We're not going to win by being the ugly Americans out there."

Bessey, a tall, athletic-looking West Point graduate from Michigan, glanced over at the stalled convoy while he settled in on a pile of rocks and waited for help to arrive. He vigorously worked a plug of tobacco in the corner of his mouth while he listened to Malik Dalawar, the Khuga Kheyl tribal elder, plead his case.

Thick-fisted and balding, with a stubbly white beard, Dalawar took Bessey's measure with a long, hard look. We need guns, he said. At night, there are few NATO forces or Afghan police or troops around to safeguard local villagers. Dalawar said he and his people needed some way to defend themselves against the Taliban and al-Qaeda fighters who regularly sweep into the area from Pakistan. But Bessey was not entirely convinced.

Dalawar, a member of the Mohmand tribe, said he is no fan of the Taliban. But in places such as Khuga Kheyl, the pressure on tribal elders to join the Taliban is intense. Electricity is scarce. Paved roads are nonexistent. And insurgent hideouts are abundant on both sides of the border. Dalawar said insurgent commanders regularly try to entice him to join the fight against coalition forces.

"They tell us to fight alongside them. They say: 'We will give you roads. We will give you electricity.' The Taliban, they tell us: 'Look, the Afghan government has given you nothing. If you fight with us, you can have everything,' " Dalawar said. "When we tell them, 'No, we will not do this,' then they tell us they will take our villages by force if they have to."

The threat in Khuga Kheyl is serious. A day before Bessey's convoy passed through the village, about 600 Afghan Taliban fighters had overrun a Pakistani military base in the Mohmand tribal area just across the border. The assault left 46 Pakistani troops dead. Regional experts and military officials speculated that many of the attackers came from an area not far from Khuga Kheyl.

"I am an elder, so if someone has a gun and I don't, I can't do anything," Dalawar said.

"If the area is secure, then you don't need a weapon," Bessey replied.

Dalawar tried again: "If something happens and I do not have an AK-47, it could be a problem."

"If you have a weapon, it could be a problem for someone else," Bessey said.

In other parts of Afghanistan, the debate over whether to arm local tribal leaders has been largely settled. In southern Afghanistan and in provinces near the capital, Kabul, where the Taliban is strongest, the training and arming of local tribal militias will soon be underway.

Nevertheless, some Afghans have said they fear that arming local militias will lead to abuses and could reignite the same intertribal frictions that sparked a protracted and brutal civil war in Afghanistan in the 1990s.

Lt. Col. Patrick Daniel Jr., commander of the U.S. battalion based in Nangahar province, said many American officers in the field support the idea of allowing responsible Afghan tribal elders to arm themselves. But such an approach carries risks and might not work in every province, Daniel said.

"For a lot of us out here, we recognize that it's much like how we feel about the Second Amendment and the right to bear arms in the States," Daniel said. "But we already have tribal disputes that are resolved by violence, and when you give them more weapons, that could mean those disputes could get resolved with those weapons. So it's a roll of the dice. Still, you can't rule it out . . . because people here need to protect themselves."

When another U.S. convoy arrived with a spare tire, Bessey deferred the decision on Dalawar's request for a few weeks, saying he would bring it up with the incoming U.S. commander in the region. He brushed the mountain dust from his pants and called for his troops to mount up.

Dalawar looked the American soldiers over one more time. He frowned slightly. The sky darkened as the sun dropped behind the mountains. He shook Bessey's hand and said he would be glad to see him again.

In Afghanistan, Terrain Rivals Taliban as Enemy

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)